Practical men, who believe themselves to be quit exempt from any intellectual influences are usually slaves of some defunct economist (Keynes, quoted in Raworth, 2017, p. 7).

By the way, the quote goes on with: Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.

In April I was asked to give a presentation after we had watched a documentary about the ideas of Kate Raworth; labelled the doughnut economy.

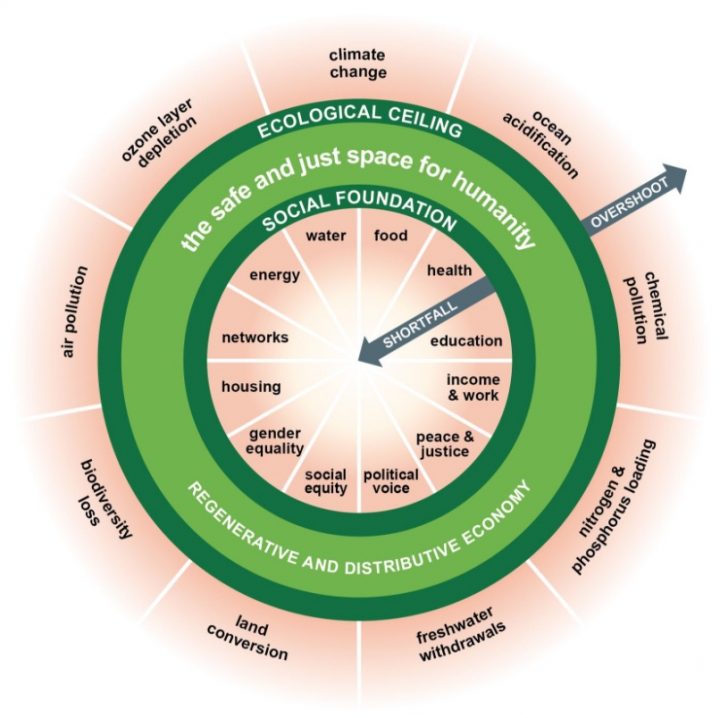

In a nutshell, the idea is that there are a set of human conditions which have to be fulfilled; these determine the social foundations of the world. Factors as clean water, education, food, but also energy, gender equality and a political voice have to be realized for all.

Yet, the production of the social foundation demands the usage of resources, the utilization of the earth. The maximal sustainable exploitation of the natural resources define the ecological ceiling. In some cases, we over utilize the resources: climate change, air pollution and the loss of biodiversity are signs that the resilience of earth is damaged.

Raworth postulates that there is a zone between the optimum social foundation and the resilience of nature, the ecological ceiling, humanity can realize its maximal living conditions, without depleting the natural resources beyond recovery: the donut is the dough between human needs and extermination of nature.

In this sense, the donut model is a classical economic model, based on a min-max solution trade-off, nature against human desires. However, the model misses any kind of first principles which explain a tendency towards the stable corridor. With first principles I mean certain assumptions about behaviour which cause movements in other variables, interacting and often moving an economy between ‘stable ’states.

For example, Keynes assumed that under consumption will lead to more savings, reducing the interest rate, which stimulates investment, raising income and so increasing consumption. (New) Classical economist belief the flexibility of prices and wages to correct mistakes and result in full employment and fair market prices. Marxist economist see the struggle between, workers and capitalists over income, resulting in stable cycles of prosperity and depression.

Furthermore, there are economic theories which try to explain why the world is as it is, and models which describe the world as it should be. Marx’s theory on capitalism is an example of the first kind, his theory on socialism an example of the second.

As Raworth often uses phrases as the government should……., firms have to…………. and consumers must……; I would label her model as one of the prescriptive kind. In her book see set several conditions for the existence of a doughnut economy: (1) Change the goal from growth towards sustainability (versus goals as GNP); (2) Keep in mind the big picture, economics are embedded in society and nature (versus independent markets); (3) Humans are imbedded in social networks (versus the homo economicus); (4) (Complex) System thinking (versus mechanical equilibrium); (5) Redistribution is more important than distribution: growth will not automatically result in a fair distribution of income and income differences are not necessary for growth; (6) Create to regenerate (versus trust in growth as the solution to all problems); (7) Growth is addictive, stagnation is sustainable.

Raworth via Twitter: https://twitter.com/KateRaworth/status/1014508070829948929

Of course, point 6 and 7 tackles my critique that she doesn’t postulate some kind of theory, as she does not believe in ‘mechanical’ equilibrium solutions. Yet, we know that people, when restricted by income and prices will try to maximize their possibilities, even if we may be criticizing their choices. Poor social choice can be rational from an individual point of view: t-shirts made in sweatshops may be socially shameful, but they are affordable!

Problem is that Raworth’s solution is that it requires a green dictatorship to solve free rider and other problems. As just described, there is the tension between social desirable and affordability. Living within the donut involves a redistribution of wealth, on an individual level, but also on a national and international level. Given the Dutch experience with ‘green farming’, taking place at this moment, such adjustments are very slowly and depending strongly on the sensitivity of the middleman. As there is no mechanical equilibrium, some an independent body should enforce solidarity, especially international: financial solidarity seems to decline with geographical distance, but there is also a prisoner’s dilemma: when the others do behave, and we don’t, we can harvest the fruits without paying the price.

When I compare Raworth’s ideas with Marx’s theories, I see at least one similarity. Marx’s theory on capitalism describes tendencies and dynamics which can be observed in modern time capitalism. However, his less founded ideas on the socialist state depended strongly on a vision of the worker as a solidary and social being, whereas the practical execution of his ideas has led to several kinds of dictatorships, with different outcomes, but never to the labourers paradise Marx expected.

So does Raworth describe several tendencies, as an emergent feeling of urgencies, an attitude of solidarity, the emergence of the sharing and caring economy. However, her solution is built on the same optimistic view of human nature as Marx.

On the other side, economists and environmentalists use her model in a descriptive way, concluded that in several countries and regions the social foundation lacks in several ways. In some regions free access to clean water is a problem, in other areas education is guaranteed, at least for boys and is gender equality a big issue. Also, in several aspects the natural resources are damaged. The amount of plastic in the oceans is threatening the survival of several species. Climate change threatens the existence of small islands, changing the living conditions of whole populations.

The documentary was interesting, although I think that the supporters of Raworth’s ideas miss some or the points, believing it possible does not make it possible!

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.